David Garrard: 'The Pub That Wouldn’t Die: A Case of Architectural Resilience'

When I was a teenage drinker in mid-90s Manchester, we used to go to a certain pub – the Old Wellington Inn, a.k.a. the Old Shambles, or just the Welly – that had, and would continue to have, a very peculiar history. Twenty years on, having devoted much of the intervening period to studying philosophy, conserving historic buildings, and/or (as in my present research) applying the former activity to the latter, the place is often in my mind. If anything got me started down my current path, perhaps it was this.

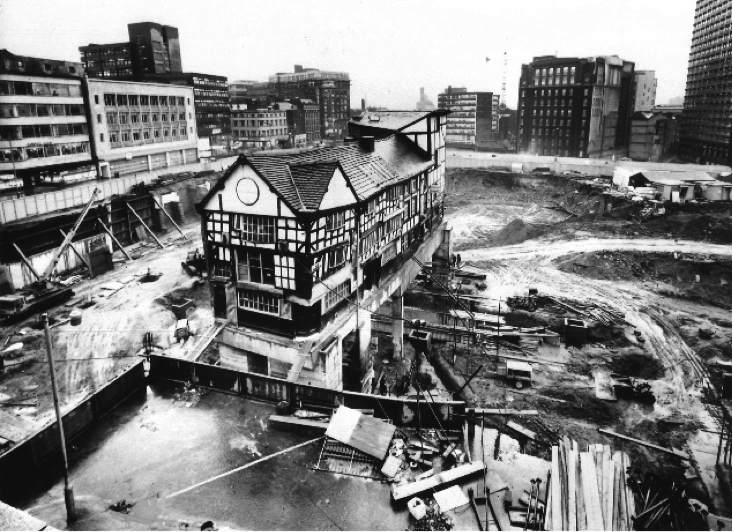

Built around the year 1550 in what was then a nondescript south-Lancashire market town, the Old Wellington was the very last of Manchester’s half-timbered vernacular buildings to survive the city’s stupendous nineteenth-century growth. Modified, extended, re-fenestrated, it clung to its little patch of ground among the tottering brick piles of the Victorian Cottonopolis, accommodating a wine merchant, an oculist, a fishing tackle shop and a series of squalid tenements. It narrowly escaped annihilation in the 1940 Christmas Blitz, but post-war rebuilding left it stranded on a traffic island, and comprehensive redevelopment in the 1970s saw it placed on a concrete raft and jacked several feet up into the air, ultimately to grace a rather bleak little plaza round the back of Marks & Spencer’s.

It was in this setting that my under-age drinking buddies and I sipped our experimental pints of Scrumpy Jack. Then, in June 1996, the IRA set off a 3,000-lb car bomb just across the street. The building was repaired at a cost of £500,000; but the City Council, in a wholly characteristic piece of joined-up thinking, then proceeded to flog off the entire site to build a Manchester branch of Harvey Nicks. By the turn of the millennium the Welly had moved again, dismantled timber by timber and re-erected – in a new configuration – in a would-be Heritage Quarter on the south side of Cathedral Yard.

There it remains, for now: the pub that wouldn’t die, proud emblem of the tenaciousness of the urban vernacular in the face of all that modernity can throw at it. But also, surely, a boundary case for the metaphysics of architectural persistence. The Old Wellington is still with us, in some sense. But whether or not it’s really the same building is a familiar topic for bar-room philosophers. In how many respects can a building change before its identity over time is decisively ruptured? Where does innate physical resilience end, and the process of institutional mummification begin? What exactly is the value of such fragments of the past – compared, say, with that of other kinds of things (man-made or otherwise) that survive down the ages? What ethical and political imperatives drive our increasing demand that such items be preserved; and where, culturally speaking, might this tendency lead?

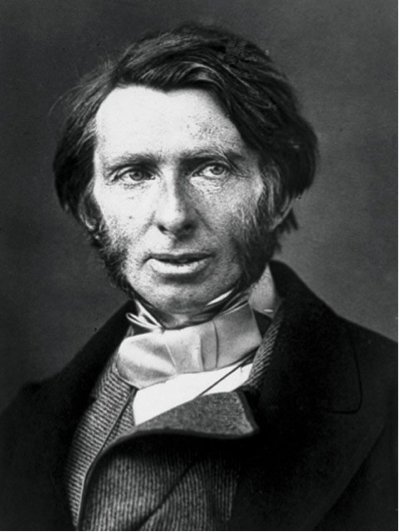

John Ruskin, preeminent Victorian critic and father of English preservation discourse, wrote in 1849 of architecture’s ‘lasting witness against men, [its] quiet contrast with the transitional character of all things’, declaring that only when a building ‘has been entrusted with the fame, and hallowed by the deeds of men, [when] its walls have been witnesses of suffering, and its pillars rise out of the shadows of death’ could its true, final meaning and value be realised. In a treatise of 1903, the great Viennese art-historian Alois Riegl, conservator-general of Habsburg Austria, suggested that ‘the monument is valuable only as a perceptible substratum whose task is to stimulate that feeling which is evoked in modern people by the inexorable ritual of being and passing away’.

On the one hand, endurance and earthly immortality; on the other, cyclicality and perpetual succession. These are the poles about which conservation thought inevitably rotates. Which makes a building like this one – a survivor, yet a shape-shifter; a safe harbour in the historical maelstrom, but one whose very location cannot be relied upon – unusually good to think with. Maybe those lost weekends down the Shambles weren’t entirely wasted.

David Garrard is a PhD student at King’s College London, where he attempts to think and write philosophically about the business of preserving old buildings. Having previously worked for English Heritage, the Victorian Society and other kindred organisations, he currently runs the MSc course in Historic Conservation at Oxford Brookes University.