'Conspiracy Theory': James Waddell interviews Lucy Sabin

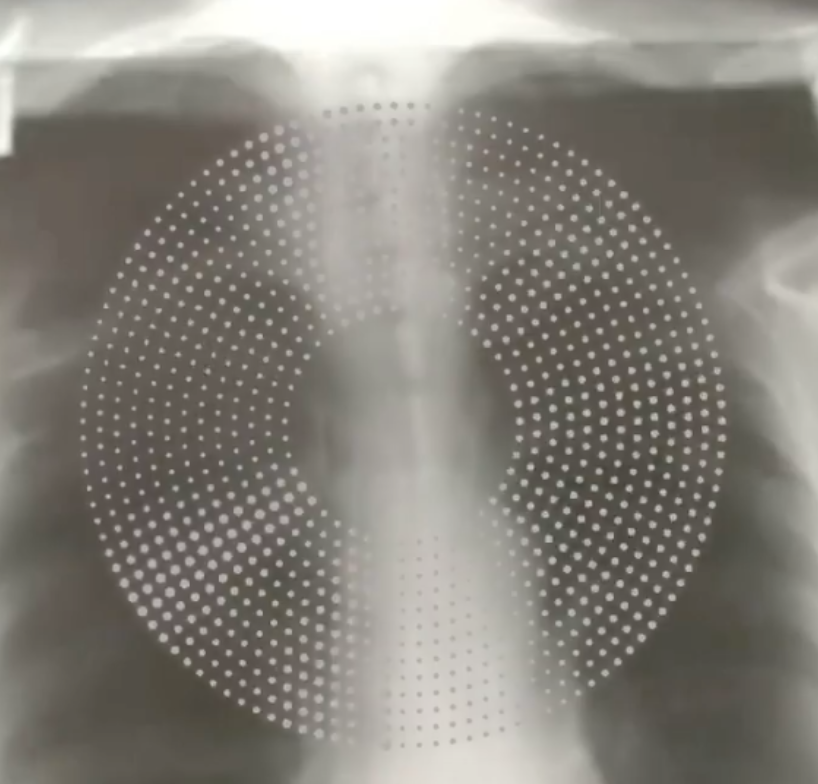

For a few minutes, I am pausing to listen to the sound of breath. Not my own, but that of others: deep, meditative inhalations with birdsong in the background, then yogic chanting, then a baby yawing, then the slow, hollow rhythm of breath in an oxygen mask. Each is accompanied by an image—a painting, a photograph, or an abstract pattern—over which a circle of dots pulses and shimmers in time to the sound, like rippling water or the surface of a booming loudspeaker. I’m watching selected contributions to Breathworks, a participatory digital artwork at Modern Art Oxford which invited members of the public to contribute one image and one sound recording which they felt conveyed their experience of breathing. The project was initiated in 2020 by Lucy Sabin, then a Creative Associate at the gallery, and now an LAHP-funded PhD student at UCL, where her creative research practice investigates breathing, air and atmospheres.

Breathworks was conceived before the pandemic, but grew into a year which brought this most inconspicuous element of our daily lives crashing into the foreground. A summer of anti-racist protests rallied around the slogan “I can’t breathe,” and an airborne virus which attacks the lungs forced us to shut down public life, in turn driving down levels of air pollution as global mobility ground almost to a halt. Discussing the intertwined quality of these events, Sabin wrote at the time:

“I mention these diverse phenomena in one sentence (or in one breath?) not to demean or conflate their ongoing, profound and complex reverberations, but to illustrate that breath is a prominent theme of 2020; it is at the forefront of our collective mind.” When I interviewed Sabin this year, she told me it was this foregrounding, this special attention to unconscious processes, which had animated Breathworks in the first place. “The interesting thing about breath was the fact that it usually might get overlooked, because it’s invisible. And maybe we take it for granted, because it happens all the time. But it also connects all of us.”

So, the purpose of Breathworks was “to give pause; that it might be a moment in which the viewer would perhaps, also, be vicariously aware of their own experience of breathing.” For many, the pandemic was a moment of revelation, where the tide of normality and routine rolled back to reveal the underlying contours and currents which were already shaping society: strong solidarity and networks of mutual support, but also structural underfunding of health services and racial disparities in medical outcomes. It strikes me that art and protest share this revelatory quality; this ability to foreground and make heard the invisible processes which underpin our lives. This isn’t to flatten or universalize, as Sabin is keen to emphasise. The contributions to Breathworks are diverse and sometimes conflicting: some are breathing deep and easy, others fighting for air. Writing about the exhibition, Sabin argued that by “Attuning to breath/lessness across time and space, we pinpoint ruptures where access to breathable spaces becomes disrupted or denied along the fault lines of power imbalances.”

Still, Sabin tells me, “breath is a really strong way of connecting people and creating empathy.” It’s also something that we (normally) do together. Taking cues from the anthropologist Timothy Choy, Sabin’s work picks up on the idea of “conspiracy,” from the Latin con meaning “with” and spirare meaning “breathe,” saying that “lately, I have committed to literally-figuratively conspiring with myself and others through creative practice.” The idea of breathing together seems to me (and probably to most) singularly unappealing at the moment, conjuring up those lab-made CGI models which periodically do the rounds on social media, showing aerosol particles moving around virtual rooms and engulfing animated stick figures. But Breathworks sought to recuperate conspiracy, and even contagion, as positive forces. Participatory art, inviting collaboration from everyone, seeks to blur the idea of an individuated creating subject, prioritising instead that which we share and co-create.

In turn, this effort engendered the curatorial practices of Breathing Worlds, an art-research project in collaboration with Derek McCormack, Professor of Cultural Geography at the University of Oxford. Breathing Worlds extended the ideas behind Breathworks into a gallery exhibition, culminating in a seven-by-three-metre “research wall,” drawing together interdisciplinary insights in images and text. The idea, Sabin says, “was that the viewer when they encounter it would be able to navigate through it in their own ways, like a cloud of research, and then they can choose which route they want to take. So you might make a connection between environmental health and public health.” Again, the work’s form mirrored its content. It was “designed to emulate how we imagined air to be, like you can think of it like water droplets in the cloud, or like particle fallout, or a molecular spaced out collage.”

In turn, these practical formal experiments fed back into Sabin’s research, which is characterised not only by academic interdisciplinarity, but also by its close relationship to artistic practice. It’s hard to label this work: “there are so many different terms for, methodologically, how you would prioritise what the outcome would be between practice and theory...I call myself an artist researcher, because I don’t want to suggest a hierarchy between the two terms. I wouldn’t ever say I’m just working in the art mode, or just working in the research mode.” In addition to drawing on both artistic and academic practices, Sabin’s work draws on her own experiences as a yoga practitioner: “my own relationship to breathing has very much been framed by the fact that my mother is a yoga teacher, and I’m a teacher. Because, you know, that’s my own embodied experience. When I think about breathing, that’s the frame.” If breath is the animating connection which breaks the boundary between our inner and outer lives, or even between ourselves and others, in Sabin’s work it also becomes a test case for how we might dissolve the artificial barricades between different forms of intellectual inquiry: in a word, an inspiration (from in meaning “into,” and spirare meaning “breathe”).

Lucy Sabin is is an artist-researcher interested in breathing and atmospheres. She is currently study- ing for a practice-related PhD with the UCL Department of Geography. More information is available on her website: www.lucysabin.world

James Waddell is the Editor of Still Point Journal, a freelance writer, and LAHP-funded PhD student in the English Department at UCL, where his research investigates attention and distraction in early modern literature and culture. He writes about books and arts for the Times Literary Supplement, The Economist, The Observer, Prospect, 1843, Elephant, and other places. He is a winner of the Telegraph/Benjamin Franklin House Literary Prize and the Art Fund writing competition, and was runner-up in the 2021 Anthony Burgess Prize for Arts Journalism.