Lewis Barnes: 'Ryuichi Sakamoto: Conserving the Future'

“I am working on things that will only be understood by the grandchildren of the 20th century.” These words, a riff on Debussy’s modernist sensibilities, open Elizabeth Lennard’s 1985 documentary Tokyo melody: un film sur Ryuichi Sakamoto. This is the Sakamoto who is often remembered: reaching excitedly towards the future. If his more sentimental and ecologically minded late works complicate this portrait of the artist as an optimist, they yet shed light on Sakamoto’s affinity with future generations.

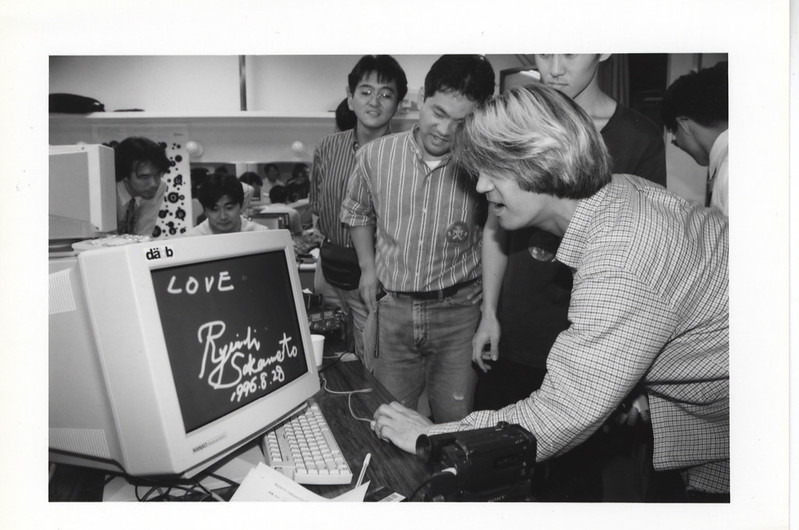

Sakamoto—the iconic Japanese composer, pianist and producer who died in March last year—stitched together a musical career which spanned six decades and countless styles, from pop to modern classical to techno. Reflecting on his work, and in particular his band Yellow Magic Orchestra’s pioneering role in the development of electronic music, novelty and technological possibility emerge as guiding obsessions in Sakamoto’s career. This is an artist whose professional pursuit of music took shape after first experimenting with synthesizers at college in the early ‘70s, who was uninterested in the traditions of his native Japan (with the exception of gagaku court music, which sounded “like aliens” to him), and who quipped that, were Mozart alive today, he would be working with the tools of virtual reality technology. His persistent club hit ‘Riot in Lagos’ (1980) conjures a well-choreographed alien invasion just as much as the automated machinic rhythms of an industrial factory. Building a new musical world with the sounds of sweeps, whirrs, glitches and pistons, the track lays the foundations for Cybotron’s first sketches of techno in 1981 and, more specifically, the funked electro-techno mutations of artists like afrofuturists Drexciya.

Tracks like ‘Riot in Lagos’ speak to “the grandchildren of the 20th century,” exemplifying—albeit from the fringes—a mood of techno-optimism typical of the 1980s and 90s. But where this structure of feeling gives way to despair in the face of accelerated environmental destruction and extractive accumulation, Sakamoto’s more recent output takes a corresponding turn.

Speaking to The New Order in 2018, Sakamoto describes a decades-long obsession with questions of the environment and conservation, an obsession which is given voice in his 2021 “opera” Time. Humanity is portrayed, through dancer and actor Min Tanaka, with a “natural passion to make a road, to conquer nature.” Surrounded by a deteriorating natural world and threatened by rising sea levels, humanity’s only response is to build new infrastructure, pursuing the same cycles of development and exacerbating the problem it is trying to solve. Highlighting these self-annihilating industrial impulses, Sakamoto’s environmentalism echoes Situationist theorist Guy Debord: “For the spectacle, as the perfect image of the ruling economic order, ends are nothing and development is all—although the only thing into which the spectacle plans to develop is itself.” With a nod to the hollow but all-encompassing logic of the market, Time exhibits a shift from the optimism of YMO’s early synth mutations towards an environmentally grounded conservationism.

The slow pace of async (2017), the album which followed Sakamoto’s recovery from throat cancer, indicates a similar perspective. In ‘fullmoon,’ Sakamoto centres a recording of Paul Bowles reading from his novel The Sheltering Sky. “How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless.” With the same passage criss-crossing in languages from across the globe, the maestro makes sense of his mortality with a rallying cry to value and preserve the simple and everyday pleasures that punctuate our lives. Dwelling on the past rather than bulldozing forward, this song swaps synthesizers for the ghostly drone of ceramic bowls. In the 2018 documentary Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda, the connection between this musical motif and the composer’s interest in constancy and preservation emerges: “I’m fascinated by the notion of a perpetual sound. One that won't dissipate over time.” While lyrically highlighting finitude, Sakamoto gestures musically to the infinite. Whatever tension might exist between these themes, both, in the context of ‘fullmoon,’ implore us to hold on.

We can trace this same impulse in Sakamoto’s attempts to merge space and sound, to bring us closer to the objects around us. Again, speaking to The New Order: “music has to do with sounds that objects make. An object always exists in some space and when it touches something, it produces a sound wave and reaches human ears, which is how a sound becomes a material for music. I am attempting to turn this thinking into the actual sound.” Whereas the Sakamoto of ‘Riot in Lagos’ and YMO was compelled by the abstract, synthetic sounds of new music technology, here his attention is turned towards the elementary technology of sound and its reproduction. Sakamoto traces the physical chain which connects the object or instrument, via the oscillations of air pressure which constitute sound waves, to our aural experience as listeners. In this light, that he plays a piano which was severely damaged by the 2011 tsunami on async is particularly striking. When we hear it, we are brought into physical proximity to the piano, its scars, and the oceanic residue still within it. Likewise, highlighting the physicality of sound lends an extra intimacy to the haunting breaths which decorate Sakamoto’s final album 12 (and which recall Glenn Gould’s divisive humming). The concrete takes precedence: his breath, right here in the room with us.

Sakamoto’s turn towards the past and the present—his interest in conserving life and beauty—mediates his optimism towards the future. But his commitment to exploring the technology of music-making is indicative of his continued interest in the possibility of a better world. The more recent projects discussed here reveal, and give a specifically musical expression to, a desire both to preserve the debris of time and human excess, and to imagine alternative routes into the future. Time’s critique of repetitive, destructive “development” is more of an attack on an empty, careless vision of progress than a call to remain stuck in the past. And though the nostalgia of ‘fullmoon’ might encourage us to hold on and slow down, its speculative appeal to the perpetual or infinite invites us to take the things we value forwards with us. In Tokyo Melody, Sakamoto ruminates on new technologies and the ability to make music in a non-linear fashion which they allow. Musical blocks can easily be moved through the chronology of a song. In music, the present can also be in the future: to conserve and protect is also to take forwards.

In April last year, musician and writer David Toop recalled a conversation with Sakamoto in which he rejected the geographical division of East and West: “My music is much more melting. All the different things are layered at the same time. It represents a sense of Utopia.” Here, Utopia is invoked not through a naive techno-optimism, but through a thoughtful, open, and non-linear acknowledgement of the possibilities presented by the world around us. In this light, we might see Sakamoto’s urges to protect, conserve and savour, still presented through a technological view of sound and music, as forward-looking. His work reflects critically on how we imagine the future in service of a more hopeful way forward, engineering the values upon which a better world can be built.

Lewis Barnes is a music fan and PhD student in London, researching state uses of automation technologies in relation to racialisation and economy.